MYSTICS AND MESMERISM IN

'THE SORCERER'S APPRENTICE'

John Hirschhorn-Smith

SIDE REAL PRESS INTRODUCTION:

The following was first published as the introduction to the Side Real Press edition of 'The Sorcerer's Apprentice' (Side Real Press 2019) and looks at various influences that might have have played a part in its creation.

The text has a few, minor, corrections but remains largely unaltered, although for ease of online reading the footnotes in the original text have been incorporated into the main body of this version of the essay. This version also has a number of added extra images and all the images are rendered in colour where possible.

Sadly, the Side Real Press editions of Ewers works are out of print but some may be available from the dealers listed on the Press' web-page.

However, the final volume of the so called 'Frank Braun trilogy' (of which 'The Sorcerers Apprentice' was the first part) 'Vampire' will be forthcoming from Side Real Press.

Sadly, the Side Real Press editions of Ewers works are out of print but some may be available from the dealers listed on the Press' web-page.

However, the final volume of the so called 'Frank Braun trilogy' (of which 'The Sorcerers Apprentice' was the first part) 'Vampire' will be forthcoming from Side Real Press.

MYSTICS AND MESMERISM IN 'THE

SORCERER'S APPRENTICE'

|

| (Cover of the original German edition) |

Recent years have seen a rise of interest in the writings of Hanns Heinz Ewers (1871-1943) with more of his works now available in English than ever before. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (originally published as Der Zauberlehrling oder Die Teufelsjäger, 1909) was his debut novel, melding Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1749-1832) eponymous poem of 1797 with a true case of religious hysteria which occurred in the Swiss Alpine village of Wildisbuch during the years 1817-1823 which is detailed in Johannes Scherr’s (1817-1886) book, Die Gekreuzigte oder

das Passionsspiel von Wildisbuch (The Crucifixion or The Passion Play of

Wildisbuch, 1860), supplemented with original police reports.

The novel is the first of what is now sometimes termed the ‘Frank Braun trilogy’, Frank Braun being an anti-hero who also appears in the novels Alraune (1911) and Vampir (Vampire, 1920).

Ewers’ lifestyle and nationalist sympathies have cast something of a shadow over his writings, which were often dismissed — both during his lifetime and since — as mere sensationalism. More recent commentary seems generally focused on two themes found within his work; the political and the occult/satanic. This essay will attempt to place the latter element, which is certainly present in Ewers’ fiction, in a more nuanced context by examining it in relation to the developments taking place across the fields of science, philosophy, psychiatry and religion — and which may have provided sources and inspiration for the novel.

I have previously given an overview of Ewers’ life and works in my introduction to Nachtmahr — Strange Tales (Side Real Press, 2009), now online at the Side Real Press website (www.siderealpress.co.uk). For those unfamiliar with either, here is a brief synopsis.

Ewers was born in Düsseldorf into a fairly affluent middle-class family with artistic leanings. He initially trained as a lawyer (receiving his doctorate in 1898) but never practised. Instead, he became involved with the bohemian circles of Berlin, performing in Berlin Cabaret (Überbrettl) and later formed his own troupe which toured Europe. His controversial repertoire, which often contained satirical and sexual material, gave him a level of notoriety that he seemed to actively embrace, and would follow him throughout his life. As a journalist, and sponsored by a travel company, he toured India and South America producing numerous articles and two books. The visit to India was made in the company of his first wife Ilna Wunderwald (1878 -1957), an artist who would later illustrate a number of his books. Ewers loathed journalism and regarded it merely as a means for a lifestyle that gave him space to write his own works.

|

| Ilna Ewers-Wunderwald |

Ewers wrote fiction for both children and adults, but it is the latter for which he is now remembered. His adult novels and stories were primarily ‘contes cruels’ with elements of supernatural/mystical horror and recurring themes of blood, transformation and perverse sexuality. His second novel Alraune (1911), ostensibly a version of the mandrake myth, was a huge success that sold half a million copies in Germany by 193 , was translated into 21 languages and filmed five times. He wrote the screenplay for that and a number of other films, most notably The Student of Prague (1913) which is widely considered the first ‘art film’ being immediately reviewed by Otto Rank, a close confidant of Sigmund Freud.

He was a spy in the U.S.A. during W.W.I, making speeches for the German cause and writing for a propaganda paper amongst other activities. He was interned as an enemy alien in 1918 and not released until 1920.

Ewers became a nationalist and joined the NDSAP in 1931. Although certainly an elitist and partially racist (he was not an anti-Semite), but his writings became more politicised and included Reiter in deutscher Nacht (Riders of the Night) and a hagiography of Horst Wessel (both 1932). The latter was supposedly written at Hitler’s request but fell foul of the Party for its content — which combined with his decadent past, ultimately resulted in the banning of his works. Ewers’ remaining years were spent in largely reduced circumstances, and he died in Berlin aged 72 on June 12th 1943, at virtually the same time as his Düsseldorf home of birth, was largely destroyed during the allied bombing.

Wilfried Kugel’s biography Der Unverantwortliche: das Leben des Hanns Heinz Ewers (The Irresponsible: the Life of Hanns Heinz Ewers, 1992) reveals that Ewers often drew from personal experience in his fiction. This is particularly apparent in Vampire where Braun’s adventures as journalist, spy and political activist closely parallel the author’s own years in America. Ewers also used his travel experiences to provide local colour, for example, the beggars diseased and deformed by various ailments such as leprosy and elephantiasis on the quayside of Port-au-Prince (which he visited in 1906) appear in the short story Fairyland (1907), a tale on the decadent theme of ‘beauty in ugliness’ in which a child happily rhapsodises on the ‘creatures’ she sees as ‘more beautiful and wonderful than anything in my book of fairy tales.’ (Fairyland.)

Ewers also uses his characters as mouthpieces to articulate his own views and opinions. This is confirmed in Brevier (1921) which was translated by Joe Bandel and published by Side Real Press in 2012. Brevier is a volume of extracts from Ewers’ published works, both fictional and non-fictional, arranged on themes such as music, art, love and religion. Although the book was compiled by Arthur Gerstel and Rolf Bongs (both old family friends) rather than Ewers himself, it should none the less be regarded as a summary of his credo at that point in time. A Breviary, in the religious sense of the term is a book containing the most important Church liturgies presented in a simple form for the laity.

|

| Cover of Side Real's ed of 'Brevier' |

In the introduction by Georg Goyert, a friend who would later translate James Joyce’s Ulysses into German, Ewers is summarized thus: ‘Ewers came to write novels from his interest in fairy tales and that they spring from an ancient part of the human psyche, a part that is much closer to the SOURCE than modern psychology is. Whoever in the deepest sense knows how to grasp fairy tales, who can give form and substance to those deep, recognizable meanings, is aware of his own ancient origins and becomes closer to the SOURCE, the Cosmic Consciousness of which each human is a part and to whom each psyche is connected.’ (Emphasis in the original.)

This theme is represented in the first quote from Ewers himself, an extract from an introduction to the artbook Musik im Bild (Music in Images, 1913) in which he specifically mentions the major themes of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

‘It is solidly established in the deepest human nature that all things new and unfamiliar are uncomfortable, while persistence along all accustomed paths brings happiness! That is why fairy tales are of ‘The Good Old Times’; the favourite songs of every generation sing of the morals and customs of our fathers and we find our poetic ideal in ‘Golden Antiquity! ’ . . . The past always appears as the victor, as the highest happiness! Back to the earliest beginning of all emotions, back to the point where a living creature had no conscious awareness of itself, could not make the distinction between itself and the exterior world. The achievement of this condition is the final atavism that there is, that which the mystical ecstatic calls, ‘Merged in God’, yes, to rest in the ‘Godhead.’ It is the final culmination of all wisdom — therefore it is entirely logical that those who hold this condition of ecstasy as the ‘highest happiness’ should not forget that this ‘highest’ is in fact the origin of everything and the deepest of everything, that fairy tales of the ‘Good Old Times’ are the most grandiose as well as the most beautiful lies that humanity knows.

I take a different position — in my book, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, an attempt is made to follow this path of thought to it last particular.’ (Music in Images.)

Many of the ideas in Music in Images are largely paraphrased from The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, but its concluding paragraphs are actually taken verbatim from Chapter twelve of the novel:

‘Music was a breath from the beyond, so much was certain.

It was only form and never substance, born of that huge sea of the negative which one calls feeling. It offered thousands of images of all the various stimulations and expressions of the will, but never the phenomenon itself, only its shadowy soul that no longer possessed any real character. It was never an image of the phenomenon, only of the will, and was thus, fundamentally, being in its uttermost abstraction. It awakened feelings the possibility of which one did not know, and the significance of which one did not grasp; things which one never saw and never would see.

To those who believed in it, it gave happiness.

Even as intoxication gives happiness, even as lust does — to those who believe in them.’ (Music in Images and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.)

|

| Friedrich Schelling |

Such division and transformation made comprehension of the Weltseele difficult (especially as the human race increasingly became more obsessed with material and sensual pursuits), and whilst Enlightenment scientists sought to dissect corporeal nature into its physical components, Romantic scientists explored, via personal experience, intuition and analogy, the ‘night-side of nature’; dreams, ecstasy (religious or otherwise), ghostly phenomena and other so called ’paranormal' experiences.

Both Enlightenment and Romantic scientists sought in their own ways for some universal element or force that united everything. Electrical experiments by the likes of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) appeared to demonstrate such a force, and coincided with the German doctor Franz Anton Mesmer’s (1734-181 ) own discovery around 1774 of a ‘universal fluid’ which appeared to have positive and negative magnetic ‘tides’ and could be found in both the celestial macrocosm and individual microcosm.

Mesmer’s discovery was seemingly validated when, in 1775, he was asked to join a committee to investigate a Swiss priest named Joseph Gaßner (1727-79) who had achieved wide fame and a large following for various healings and exorcisms that he carried out using methods very similar to Mesmer’s own. Mesmer reproduced Gaßner’s effects, inducing and curing convulsions (which Mesmer termed crises) and the committee concluded that Gaßner (though honest) was unknowingly using Mesmer’s universal fluid rather than divine powers to effect his cures.

Both Enlightenment and Romantic scientists sought in their own ways for some universal element or force that united everything. Electrical experiments by the likes of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) appeared to demonstrate such a force, and coincided with the German doctor Franz Anton Mesmer’s (1734-181 ) own discovery around 1774 of a ‘universal fluid’ which appeared to have positive and negative magnetic ‘tides’ and could be found in both the celestial macrocosm and individual microcosm.

|

| Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-181 |

Mesmer’s discovery was seemingly validated when, in 1775, he was asked to join a committee to investigate a Swiss priest named Joseph Gaßner (1727-79) who had achieved wide fame and a large following for various healings and exorcisms that he carried out using methods very similar to Mesmer’s own. Mesmer reproduced Gaßner’s effects, inducing and curing convulsions (which Mesmer termed crises) and the committee concluded that Gaßner (though honest) was unknowingly using Mesmer’s universal fluid rather than divine powers to effect his cures.

Thus endorsed, ‘Mesmerism’ (as it then became known) achieved something of a craze, especially when Mesmer relocated to Paris in 1778. His fashionable and expensive treatments would ultimately include rooms with mirrors to ‘reflect’ the fluid back onto the patients and as the fluid was ‘communicated, propagated, and increased by sound’, aetherial music was played on the newly invented glass armonica. Patients were treated en-masse and those who succumbed to the suggestive atmosphere were taken to special padded ‘crisis rooms’ in which Mesmer would re-align their polarities using an iron wand.

Although the results were impressive, the underlying science was regarded as suspect and in 178 his claims were scrutinized by a French Royal commission led by the astronomer Jean-Sylvain Bailly (1736-93), the chemist Antoine Lavoisier (1743-94) and Benjamin Franklin, who concluded that Mesmers’ cures were effected through ‘imagination’ rather than an intangible fluid.

Mesmeric practice itself was also riven when the French Count, Armand Marie Jacques de Chastenet de Puységur (1751-1825) discovered that identical results could be achieved without magnets and concluded that the magnetizer’s own ‘animal magnetism’ (rather than a universal fluid) was responsible. He also noticed that there was a peculiar state of ‘lucid sleep’ in which patients seemed to attain a higher sense of awareness which he named ‘artificial somnambulism.’ Thus Mesmerism split into the ‘fluidist’ school of Mesmer and the ‘animist’ school of de Puységur, a divide that still remains today. As an aside, De Puysegurs brother, Antoine-Hyacinth would introduce Mesmerism to Haiti in 1784 where it was quickly integrated into Voodoo before being officially banned in the run-up to the Haitian revolution.

Tainted by the connotations of charlatanism and anti-rationalism, the study of Mesmerism by Enlightenment scientists, especially in France, waned; but some Romantic philosophers such as Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert (1780-1860) saw the Mesmeric trance as an ‘intervention of the future, higher existence in our present less complete existence.’ (Gotthilf Schubert (1780-1860), Ansichten von der Nachtseite der Naturwissenschaft (Views from the Nightside of Science), 1808).

| ||||||

| Friedericke Hauffe by Gabriel von Max 1895 |

The former detailed the life and visions of Friedericke Hauffe (1801-1829), who lived in a largely semi-somnambulistic state as an in-patient at Kerner’s house during which she experienced daily visions of the life of Christ and the Virgin,prophesied future events and received messages from discarnate entities in a tongue she claimed was the original language of mankind.

Brentano’s volume was dedicated to the visions of the stigmatic nun Anna Katharina Emmerick (1774-1824) one of Joris-Karl Huysman’s favourite mystics who was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2004. Brentano’s book included her visions of the lives of Christ and the Virgin, meetings with saints and her own battles with the devil in various forms. Both publications were seriously debated by philosophers and theologians. Crowe refers to both women in her own famous study The Night Side of Nature (1848).

Mesmerism also resonated with both the followers of Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), who saw within it a scientific rationale and method for communicating with the upper spheres of Swedenborgian practice and the more occult/mystically orientated groups such as the Martinists. Mesmerism’s somnambulistic side effects such as glossolalia, seemingly prophetic/clairvoyant insights and communication with the dead, had obvious occult/religious similarities and connotations.

Artists and poets had long used dreams and visions as a source for their inspiration and mystics throughout the ages had also attributed inspiration to come from somewhere beyond their normal existence; so it is unsurprising that Romantic theories quickly permeated these communities, influencing in the first instance the likes of writers such as Goethe, ‘Novalis’ (1772-1801), William Blake (1757-1827), Samuel Coleridge (1772-1834) and Percy Shelley (1792-1822). Shelley expressed poetry as ‘at once the centre and circumference of knowledge; it is that which comprehends all science, and that to which all science must be referred. It is at the same time the root and blossom of all other systems of thought; it is that from which all spring, and that which adorns all.’ (Shelley, A Defence of Poetry, 1821.)

A writer who would be a great influence upon Ewers was the Polish author, anarchist, and self-proclaimed Satanist, Stanislaw Przybyszewski (1868-1927), who also mentions Emmerick in his discussion of the soul. ‘The soul is that organ which comprehends the infinite and boundless; the organ in which Heaven and Earth flow together; the organ, with the aid of which a Katharina Emmerick, [describes] the site where Christ suffered, and portrays the torments of the Crucifixion with the specialized knowledge of a physiologist. It is that organ of visionary ecstasy and somnambulant clairvoyance, the organ of greatest erethism, in which Rops has created his Sataniques and Chopin his Sonata in B minor.’ (Przybyszewski, Auf den Wegen der Seele, (On the Paths of the Soul, 1897.)

Przybyszewski also explains the difference between ‘mind’ and ‘soul’; ‘The soul is unique and indivisible, its conscious part requires several of those poor senses, but beyond these senses lies a single, indivisible organ, in which millions of senses intermingle, in which each phenomenon appears in all its qualities, it appears as a unity and the absolute.’ (ibid.)

Ewers explores the theme of synesthesia (where one sense is simultaneously perceived as if by another sense) in Aus dem Tagebuche eines Orangenbaumes (From the Diary of an Orange Tree, 1907), but integrates it with another aspect of Przybyszewski’s philosophy — that of Woman as a ‘cosmic force.’ In the story the narrator believes that he is turning into an orange tree through his love for, and influence of, the supernatural being Emy Steenhop. ‘Thought does not only exist in humans, if you will, but is also capable of penetrating everything else that is physical. Why wouldn’t we find it in the trunks, leaves and blossoms of an orange tree? . . . No hour goes by, no second, in which thought is not revealed larger and more majestic than before. Ever more and more we recognise this concept . . . a thought never bears fruit in one brain alone. But the semen of the spirit is withered in many, and only blossoms in a few (From the Diary of an Orange Tree). The protagonist also speaks of physical matter changing and that ‘not-being’, i.e. death, is the only essence of ‘all matter’, but that thought remains unchanging: ‘Isn’t it much truer to speak of these thoughts as reality than it is of fleeting matter?’(ibid.) Later the narrator reads his poem ‘Orchids’ (written by Ewers six years earlier in 1900), which he describes as ‘Devils flowers’ propagated from the venom of the snakes that emerge from Lilith’s mouth when she laughs. She laughed when:

‘She had read Bourget

And loved Huysmans

When she understood Maeterlinck’s silence

And her soul bathed

In the colours

of Gabriele D’Annunzio’ (ibid.)

All the authors mentioned Paul Bourget (18 2-1935), Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) and Gabriele D‘Annunzio (1863-1948) are synestheseists and the story continues in a similar manner; Emy saying at one point ‘You don’t need to speak. I can smell your thoughts’, as the narrator transforms into another material state.

The influence of Mesmeric theories in the fiction of the time is too vast a topic for this article, but early works include Charles de Villers’ The Magnetiser in Love (1787); Frédéric Soulié's The Magnetiser (1834) and especially E.T.A. Hoffmann’s tales The Magnetiser and The Golden Pot (both 1814), and The Sandman (1816).

Later examples include Alexandre Dumas (père), The Mesmerists Victim (an episode within The Queen’s Necklace 1849), in which the Joseph Balsamo character the novel is based on Count Cagliostro (an Italian adventure and self-styled magician), Honoré de Balzac’s Ursule Mirouët (1841), Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s A Strange Story (1862) and, perhaps the most famous, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Facts In The Case Of M. Valdemar (1845), originally titled Mesmerism in Articulo Mortis, which some readers believed to be a factual account. An earlier Poe tale, Mesmeric Revelation (1844), was the first of his tales to be translated into French by Charles Baudelaire.

Scientific interest into both Mesmerism and trance/ecstatic states would be largely revived in the 1880s by the pioneering work of the neurologist Jean Martin Charcot (1825 -1893), who was the Director of L’Hôpital Salpêtrière in Paris, then one of the largest hospitals in the world.

All the authors mentioned Paul Bourget (18 2-1935), Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) and Gabriele D‘Annunzio (1863-1948) are synestheseists and the story continues in a similar manner; Emy saying at one point ‘You don’t need to speak. I can smell your thoughts’, as the narrator transforms into another material state.

The influence of Mesmeric theories in the fiction of the time is too vast a topic for this article, but early works include Charles de Villers’ The Magnetiser in Love (1787); Frédéric Soulié's The Magnetiser (1834) and especially E.T.A. Hoffmann’s tales The Magnetiser and The Golden Pot (both 1814), and The Sandman (1816).

Later examples include Alexandre Dumas (père), The Mesmerists Victim (an episode within The Queen’s Necklace 1849), in which the Joseph Balsamo character the novel is based on Count Cagliostro (an Italian adventure and self-styled magician), Honoré de Balzac’s Ursule Mirouët (1841), Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s A Strange Story (1862) and, perhaps the most famous, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Facts In The Case Of M. Valdemar (1845), originally titled Mesmerism in Articulo Mortis, which some readers believed to be a factual account. An earlier Poe tale, Mesmeric Revelation (1844), was the first of his tales to be translated into French by Charles Baudelaire.

| |

| Jean Martin Charcot |

Charcot’s observations and innovative clinical work had played a major role in the identification and understanding of diseases such as Parkinson’s and Multiple Sclerosis and it was during his work on epilepsy that he noticed that some hysterical patients would imitate the epileptics. From this he concluded that the former had a hitherto unnoticed disease of the nervous system he named hystero-epilepsy, whose ‘attacks’ followed four distinct stages that he termed Epileptoide, Grands Movements, Attitudes Passionelles and Delerium.

Believing hystero-epilepsy was an organic condition, he experimented on patients with various narcotics including opium, ether, chloral, and amyl nitrate alongside physical ‘interventions’ such as surgery and the fearsome ‘ovarian compressor’, which harked back to the idea that hysteria (from the Greek hystera = uterus) was solely a female malady caused by a ‘wandering womb.’ He would later acknowledge that men could also suffer from the disease. Their compression points were the testes.

As the nervous system had an electrical constituent, he also experimented with the influence of metals, electricity, magnets, and ultimately Mesmerism, which had been ‘rebranded’ as hypnosis in the 18 0s by the English doctor James Braid (179 -1860). He thought that the trance state was more akin to a state of sleep (hypnos) and wished to distance it from various forms of lay practice, such as ‘Heilmagnetismusa’ (therapeutic magnetism).

Charcot believed hypnosis created an artificial version of hystero-epilepsy and ultimately came to believe that the ability to be hypnotised was a symptom of a hysteric. Because the hypnotic state could be controlled, it was also a useful research and demonstration tool and in 1882 he successfully presented his findings to the French Academy of Science. The acceptance of his work was largely responsible for the rehabilitation and legitimisation of hypnosis within the medical profession and helped Le Salpêtrière become a powerful and influential institution with modern teaching aids and a staff that would include Georges Gilles de la Tourette (18 7-1904), Joseph Babinski (18 7-1932), Désiré-Magloire Bourneville (1840-1909), Pierre Janet (18 9-1947), and briefly, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939).

Charcot presented demonstrations of his researches at Tuesday and Friday morning lectures, the latter open to the general public. He had the showman’s instinct for presentation using dramatic lighting and slide projectors, mimicking the traits of patients and fixing long feathers to the hats worn by sufferers of nervous tremors to distinguish their specific characteristics. However, it was the spectacular demonstrations of hypnotised patients mimicking grand hysteria that gripped the scientific and popular press, who nicknamed Charcot ‘the Napoleon of neuroses’ and made the Friday lectures at Le Salpêtrière a fashionable destination for the rich and famous.

|

| A Clinical lecture at the Salpêtrière by André Brouillet (1887)- The woman is Marie Whittman |

A large number of books were issued by Charcot and his followers including the volumes of Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière (The Photographic Iconography of the Salpetriere, 1877-80), edited by fellow physicians Désiré-Magloire Bourneville and Paul Regnards, Paul Richer’s Études cliniques sur l'hystéro-épilepsie ou grande hystérie (Clinical studies of hysterio-epilepsy and grand-hysteria, 1881) and Les Démoniaques dans l'art (The Demonic in art, 1887) by Bourneville and Richer.

|

| Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière |

In them, the case histories of Salpêtrière patients, including transcripts of their sexual/religious reveries, were juxtaposed with similar biographies, visions and ecstasies of saints, witches and other ‘possessed’. Some volumes were illustrated with ancient images of saints and mystics alongside drawings and photos of patients in similar beatific or demonic postures. Some of these photos were titled in deliberate pseudo-religious terms such as ‘Passionate Attitudes: Amorous Supplication’, ‘Ecstasy’, and ‘Crucifixion’ and the images of (sometimes) beautiful young patients in states of hysterical dishabille added an undoubted erotic frisson and made them famous in their own right. Photos of one, ‘the delicious Augustine’ would later appear in Breton and Aragon’s La Revolution Surrealiste (1928) as part of a fiftieth anniversary tribute to hysteria — “the greatest poetic discovery of the end of the nineteenth century”.

Bourneville also oversaw the production of a series of books called Bibliothèque Diabolique (Library of the Diabolical), which included historical surveys of the witches’ sabbath, demonic possession, religious miracles, the convulsionists of Saint-Medard cemetery and the case of Belgian stigmatist Louise Lateau (1850-1883), who was still alive when the book was published, all with commentaries promoting Charcot’s theories.

|

| Illustration of a demoniac by Rubens (left) next to an illustration of a fit undergone Salpêtrière patient Genevieve Basile Legrand (1843-date unknown) |

Such was Charcot’s influence that it would be some years before his hypnotic/hysterical theories were discredited. This was primarily led by French neurologist Hyppolyte Bernheim (1840-1919) and others based at the University in Nancy, who believed that hypnotism was a psychological state that could be successfully induced in non-hysterics and that Charcot’s hysterical attacks, with their defined ‘stages’, were influenced by other factors such as suggestion from other patients and outright fraud.

|

| Periode Terminale; Extase. Photo of Genevieve Basile Legrand (1861 - ?) taken by Paul Regnard. Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (1877). (Image:Wellcome Collection.) |

This debate became very bitter and public with the respective schools appearing in court cases where there was an alleged hypnotic aspect to the case. If Charcot was right, the victims of hypnosis were hysterics and had no free will. If Bernheim was right, the victims had been psychologically manipulated and were thus ‘normal’ people.

Ultimately the Nancy school was proven right as the new emerging theories and practises of what would become known as dynamic psychiatry gained ascendancy. This was led by the likes of Albert Moll (1862-1939), Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920), Pierre Janet (1859-1947) and Sigmund Freud, whose groundbreaking book Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams) was published in 1899.

It was both aided, and simultaneously undermined, by the emergence of psychology’s dark twin, parapsychology, which also sought to apply scientific principles to unravel the occult and ‘paranormal’ phenomena that was witnessed by spiritualists, Theosophists and other occult groups, all of which were undergoing a period of popular revival. In response, the medical profession set out to rescue/wrest hypnotism and magnetism from the unscientific and potentially dangerous arenas of the music hall and séance room, by campaigning for stage-show hypnosis to be banned and lay practitioners to be regulated.

Charcot, the debate around his theories and the perceived dangers of the trance state, generated a huge number of hypnosis and hysteria related novels, some of which were perceived by both the popular and medical press as accurate portrayals of such conditions and were subsequently cited as ‘examples of type’ in medical research papers.

Examples include two novels by Charles Richet, a French psychologist and future Nobel prize winner who had interned under Charcot, written under his pen name ‘Charles Épheyre’: Possession (1887) and Sœur Marthe (1890). Charcots’ friend Jules Claretie’s, Les Amours d‘'un interne (1881) was set within the Salpêtrière itself and his novel Jean Mornas (1885), a story concerning post-hypnotic suggestion, was almost banned in Germany as it was seen as being too close to reality. Another friend of Charcot’s, Alphonse Daudet, dedicated his novel of religious fanaticism, L’Evangéliste (1883) to him but his son Léon, who disliked the physician, would later pen Les Morticoles (1894), a bitter expose of Charcot and the Salpêtrière.

Guy de Maupassant (who may have attended the Friday lectures) name-checks Charcot in his story Magnétisme (1882) and also appears to draw on Charcot and the Salpêtrière in his famous story of madness, Le Horla (1887). Camille Lomonnier‘s L'hystérique (188 ), a bodice ripper in which a stigmatic Beguine nun is seduced by an immoral abbé, is obviously inspired by the stigmatic Louise Lateau and Urbain Grandier (1590-1634) of Loudun, a Catholic priest who was burned at the stake following the ‘Loudun Possessions’. L'hystérique is quite mild compared with Henri Nizet’s sexually graphic Suggestion (1891), a ‘novel of hysteria’, set in Romania. Henri’s sister Marie Nizet’s novel, Le Capitaine Vampire (1879) also features a mesmeric episode and is sometimes cited as an influence on Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), the latter name-checking Charcot during a conversation between Professor Van Helsing and Harker regarding the paranormal. Conan Doyle, who had had an interest in hypnosis dating back to mid 1880s, depicts a hypnotic battle between the disbelieving Doctor Austin Gilroy and the manipulative medium Helen Penelos in his somewhat neglected novella, The Parasite (1894).

Marie ‘Blanche’ Whitmann (1859–1913), one of Charcot’s most famous patients and the model for the famous painting A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (1887), (a reproduction of which hung in Freud’s office) was an inspiration for André de Lordes play A Lesson at Salpêtrière (1908) and also for the actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), who was an habitué at the Charcot lectures and once installed herself in the Salpêtrière cells as part of her preparations for a performance. Another performer, the can-can dancer immortalized by Toulous Lautrec, ‘Jane Avril’ (born Jeanne Beaudon, 1868-1943) had actually been a patient at Salpêtrière, ironically diagnosed with the neurological disorder Sydenham’s chorea better known as St Vitus’ Dance.

|

| 'Jane Avril' (1890) by Paul Sescau |

By far the most famous depiction of hypnosis was George du Maurier’s hugely successful novel Trilby (1894), a book responsible for the creation of the term ‘svengali’ and the eponymous hat. One of the best-sellers of the nineteenth century it is seldom read today partly because of its cloying sentimentality but mainly because of its racist portrayal of the Jewish villain Svengali. It tells the story of a poor artist’s model in bohemian Paris who is hypnotised by Svengali in order to make her an international singing superstar ‘With one wave of his hand over her — one look with his eye — with a word — Svengali could turn her into the other Trilby, his Trilby and make her do whatever he liked . . . ’ (Trilby).

Trilby’s character was partly based on an opera star of the mid-nineteenth century, Jenny Lind (1820-1887), ‘the Swedish Nightingale’, who had herself been a participant in a demonstration of singing under hypnosis when she met James Braid during a tour of England in the 1840s. In a private demonstration at his home, he hypnotised a young woman to accompany Lind in singing songs in Swiss, German and Italian (languages the ‘uneducated girl’ did not know), but which she caught ‘the sound of both words and music, and imitating them so quickly, that it was scarcely possible to detect that both were singing’. (James Braid, Magic, Witchcraft, Animal Magnetism, Hypnotism and Electro-biology, (1852). A real-life example of a 'Trilby' style creation can be found in the performances of the ‘traumtanzeren’ (sleep dancer) ‘Magdeleine G[uipet]’. Organized by the psychic researcher Albert Schrenck-Notzing (1862-1928), Magdeleine, who supposedly had no formal training, performed her dances ‘released from earthly ties, free and spontaneous, capable of emotion and expression’ in trances induced by the hypnotist Émile Magnin. Images of these later appeared in his book, L’Art et l’Hypnose. Interprétation plastique d’œuvres littéraires et musicales (Art and Hypnosis. Plastic Interpretation Of Literary And Musical Works, 1906). Another parapsychologist friend of Schrenck-Notzing, the painter Albert von Keller (1844-1920) painted various images of the hypnotised Magdeleine, and other artists such as Alfons Mucha (1860-1939) also hypnotised their models for similar ends).

|

| Magdelaine G interprets Chopin from L’Art et l’Hypnose. |

|

| Baraduc's 1907 image of his wife Nadine taken twenty minutes after her her death |

Là-Bas was partly written as a response to medical rationalisations of mysticism, as an 1890 letter to the Abbé Boullan (a Roman Catholic Priest and occultist who appears in the book as ‘Dr. Johannes’) demonstrates: ‘I am not less weary of the systems of Charcot, who did want to convince me that the demonianism and Satanism is just an atavism that he can check or develop with the women treated at la Salpêtrière. . . I want to show Zola, Charcot, the spiritualists, and the rest that nothing of the mysteries which surround us has been explained. If I can obtain proof of the existence of the succubi I want to publish that proof, to show that all the materialist theories of Maudsley and his kind are false, and that the devil exists, that the devil reigns supreme, that the power he enjoyed in the middle ages has not been taken from him, for today he is the absolute master of the world, the Omniarch . . . ’ (Selected Letters of J.K. Huysmans ed. Barbara Estelle Beaumont). This letter is largely paraphrased in the final paragraphs of Chapter nine of Là-Bas with the questioning coda, ‘Is a woman possessed because she is hysterical, or is she hysterical because she is possessed? Only the Church can answer. Science cannot.’

Ewers took a keen interest in the interplay between these elements, drawing on all of them for his fiction and underpinning them with a philosophy drawn from Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Przybyszewski and Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860).

The latter had suggested that men of genius have an intellect that allows them to intuit the grander scheme of things and that the great artists are able to render these ideas in a form (ie, a painting, novel or piece of music) that the average person can understand. Przybyszewski believed it was the artist’s duty to ‘recreate the soul in all its manifestations, independent of whether they are good or bad, beautiful or ugly.’ (On the Paths of the Soul.)

Ewers saw himself as endowed with both the scientific methodology and the imagination/ability to be able to do this and subscribed to the French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s (1854-1891) famous pronouncement on the ‘derangement of the senses’ as a way to ‘loosen the shackles’ of earthly mundane reality. ‘Hunger — thirst — castigation — these were always the means toward this great end. Panic fear and berserker rage — how often did they precede ecstasies. And music and drunkenness and all stimuli toward violent emotion must serve here too...Ecstasy was a reversal to the conditions of the lowest animal life, in which stimuli did not occasion the formation of representations but released the reaction immediately . . . in which the will and the representative faculty were undivided and all the frontiers of the external world obliterated’ (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice).

It is thought that Ewers’ interest in hypnotism began in the late 1880s and it would appear that he had hypnotised at least two girlfriends, Erminia Tappen about 1896/97 and Helene Schleifenbaum around 1900 — the former for some sort of sexual pleasure.

If one is to believe the idea of Ewers’ fiction as partially autobiographical, then his stories Kitty's Liebe (Kitty’s Love) and Liebe (Love) (both written in 1899) may shed light on these early experiences.

Love is told in the form of a letter from an unnamed character to a friend named Lili and describes the seduction of an eighteen-year-old girl:

‘Palomita, as usual, lay stretched out on the sofa. We said hello, kissed each other. Suddenly, as my hand went over her temples, she sighed; she seemed to fall asleep. I stroked her a few times over the forehead — really she was sleeping. . . I kissed her curls, her eyes, her mouth, her hands. And then — oh I hardly knew what I was doing — I tore her dress open and covered her white breasts with kisses. And every day I let her fall asleep; when we were alone, every day. On June 24, the sun was glowing in the sky, oh it was glowing. And on that day my blood chased and pulsed like it never did. I came to Palomita. Mrs. Klara left, and she was sleeping in my arms. It happened. I took off her clothes, skirts and shirt, I took everything away from her. She did not move. And then I took her sweet innocence — she did not resist, her eyes remained closed. Only a small cry came from her lips.’ (Love.)

Eventually, the narrator confesses this to her only to discover that she in fact pretended and wanted to be seduced anyway, ‘Oh, a smile — so devilishly so vulgar . . . and in that smile, she told me that she knew everything, that she had cheated on me, lied to and deceived so fiercely, like no woman ever betrayed a man!’ (ibid.)

Lili was Ewer's pet name for Helene Schleifenbaum and within the story the narrator reminds the fictional Lili ‘For more than

two years I had not hypnotized, not since Munich. You remember, Lili,

there it was our daily game!’

Around 1896 Ewers and the painter Wilhelm Wunderwald (1870–1937), the brother of Ilna Wunderwald, became short-lived members of the Düsseldorf branch of a ‘Psychological Society’, which had been established in October 1895. These Societies were founded in Germany at the end of the 19th century by Maximilian Ferdinand Sebaldt (1859-1916). Sebaldt, who published under various pseudonyms, was a proponent of ‘sexual magic’ but the ‘Psychological Societies’ were spiritualist in nature.

Ewers and Wunderwald acted as mediums in various sèances but it would appear that their membership was something of a prank and Ewers was expelled in 1897 for bringing the society into disrepute. From various records it would appear that he would go into trance and receive messages from the likes of Heinrich Heine and Frédéric Chopin. The messages got more and more outrageous/unlikely and outraged members actually got into a fight with Ewers, to which the police were called. The so-called ‘Düsseldorf Spiritist Affair’ ended with Ewers being sentenced to four weeks ‘fortress arrest’ — a form of minimum security imprisonment (also known as ‘honourable custody’) generally used for prisoners of higher social strata.

It not known if Ewers was ever a formal member of any Masonic or other occult group but Wilfried Kugel’s biography reveals that Ewers contributed to various ‘lebensreform’ (life reform) journals including Sebaldt’s ‘Die Schönheit’ (‘The Beauty’) and ‘Das Leben’ (‘The Life’), Ewers contributing to the latter under the pseudonym ‘G. Herman’. Among articles promoting nudism and sexual liberation (Ewers was an enthusiastic proponent of both) they also contained pieces on alternative medicine and other ‘occult’ subjects.

He also wrote for Guido von List’s (1848-1919), satirical anti-Catholic magazine ‘Der Scherer’ (‘The Pest Controllers’) which later developed distinct nationalist and anti-Semitic undertones (List is sometimes referred to as the grandfather of National Socialism) as the völkisch elements of lebensreform were subsumed by a more strident nationalism.

Ewers interest in the occult would also have been stimulated by his association with writers such as Max Dauthendey (1857-1918), Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915) and Przybyszewski, all of whom had occult/mystical leanings. Dauthendey was connected to the Parisian branch of the Golden Dawn headed by British occultist Samuel Liddel (MacGregor) Mathers (1854-1918) and Przybyszewski edited and contributed to various occult magazines. Ewers dedicated his book Edgar Allan Poe to Gustav Meyrink (1868-1932), the Austrian author best known for his novel ‘The Golem’, (1915) who was a Theosophist and connected to the Golden Dawn. It is said that Ewers contacted an early incarnation of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) in 1906, which had strong links to both Masonry and Papus’ Martinist group. Both The Golden Dawn and O.T.O. are inextricably linked with the controversial British occultist Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), but there is no indication that there was any personal contact between the two until W.W.I when both worked in the U.S.A. for the pro-German propagandist newspapers The Fatherland and The International (both edited by the American author George Sylvester Viereck, 1884-1962) (the author of a 1907 ‘psychic vampire’ novel, The House of the Vampire) and during which time Ewers was also working for the German secret service.

It would appear that Ewers and Crowley had little direct communication after Ewers’ internment as a P.O.W. in 1918. He is absent from Richard Kaczynski’s ‘definitive’ Crowley biography Perdurabo (2002) and Tobias Churton’s Aleister Crowley in America: Art, Espionage, and Sex Magick in the New World (2017). However in the latter’s Aleister Crowley: The Beast in Berlin (2014), Churton quotes a letter from Crowley to a German friend Carl Germer in June 1930 in which he says ‘Please cultivate Ewers. He is really the great man’. Churton also quotes a Crowley diary entry from November the same year in which Crowley ponders whether Ewers might translate his Gnostic Mass (a key text in Crowley’s cult of Thelema) into German. Both sound potentially promising, but Churton fails to expand on either. Both authors fail to mention that Mandrake Press (a major publisher of Crowley in the late 1920’s) were seriously considering issuing Alraune (using the Guy Endore translation issued by John Day) to be possibly published under the title The Artificial Child. This plan collapsed when the firm was forced into liquidation in 1930. Whether Crowley, who was on the Mandrake board at the time, had a hand in Ewers’ selection is yet another intriguing possibility. That Ewers scarcely figures in either Kaczynski or Churton probably shows how little importance they attach to Ewers as a player on the Crowley stage, but this might also reflect a) the paucity of the material on Ewers in the Crowley archives and/or b) how slight the Crowley/Ewers acquaintance really was. It is certainly hard to detect any specific Crowley influence in Ewer’s work.

Certainly, Masonry (or at least its followers) had been mocked in Ewer’s 1904 story Die Weise Madchen (The White Maiden) in which various jaded ‘men of the world’, the narrator, a priest, a painter and a newspaper editor, attend a performance organised by Duke Aldobrandindo in which a nude barely pubescent girl tears a white dove apart over her head and is covered with its blood. For the onlookers it is a spectacle with no spiritual content, the editor will use it as a mere gambling aid; ‘“18 = blood, 4 = dove, 21 = virgin ...I will play them this week in the lottery!”’ (The White Maiden).

It is also unknown if Ewers ever used any form of self-hypnosis as part of his creative process. However, there is an intriguing letter to Ewers from Viereck dated January 29, 1918, in which he asks Ewers to collaborate on a projected book calledthe theme of which was to be that of the wandering Jew. In it, he writes: ‘It was begun under peculiar circumstances. You will remember I had asked our mutual friend Professor Müensterberg, [Hugo Müensterberg, 1863-1916, a German-American psychologist and suspected German spy] to hypnotise me so as to make it possible for me to concentrate on the task in spite of the many distractions which diverted my mind in the early days of the war. He consented and under the spell of his suggestion I completed the prologue and the larger part of the first fourteen chapters.’ (Letter dated January 29, 1918. George Sylvester Viereck Papers, University of Iowa.) For reasons unknown the Isaac Laqudem collaboration never came to fruition and Viereck later completed the novel with Paul Eldridge (1888-1982) and finally saw publication in 1928 as My First Two Thousand Years. It is unknown what, if any, Ewers influence remained within it.

What is certain is that Ewers did use various drugs recreationally and as a means of inspiration. By the early 1900s he had begun working on a book titled Raush und Kunst (Intoxication and Art) and whilst this was never completed (an as yet unpublished reconstruction has recently been completed by Wilfried Kugel) an essay of the same title did appear in 1906, which perhaps gives us a flavour of the larger projected work. It is also possible that his essay Edgar Allan Poe (also published the same year) might have constituted a chapter of this volume, as both explore the same theme in similar and, in one case identical, words.

Around 1896 Ewers and the painter Wilhelm Wunderwald (1870–1937), the brother of Ilna Wunderwald, became short-lived members of the Düsseldorf branch of a ‘Psychological Society’, which had been established in October 1895. These Societies were founded in Germany at the end of the 19th century by Maximilian Ferdinand Sebaldt (1859-1916). Sebaldt, who published under various pseudonyms, was a proponent of ‘sexual magic’ but the ‘Psychological Societies’ were spiritualist in nature.

Ewers and Wunderwald acted as mediums in various sèances but it would appear that their membership was something of a prank and Ewers was expelled in 1897 for bringing the society into disrepute. From various records it would appear that he would go into trance and receive messages from the likes of Heinrich Heine and Frédéric Chopin. The messages got more and more outrageous/unlikely and outraged members actually got into a fight with Ewers, to which the police were called. The so-called ‘Düsseldorf Spiritist Affair’ ended with Ewers being sentenced to four weeks ‘fortress arrest’ — a form of minimum security imprisonment (also known as ‘honourable custody’) generally used for prisoners of higher social strata.

It not known if Ewers was ever a formal member of any Masonic or other occult group but Wilfried Kugel’s biography reveals that Ewers contributed to various ‘lebensreform’ (life reform) journals including Sebaldt’s ‘Die Schönheit’ (‘The Beauty’) and ‘Das Leben’ (‘The Life’), Ewers contributing to the latter under the pseudonym ‘G. Herman’. Among articles promoting nudism and sexual liberation (Ewers was an enthusiastic proponent of both) they also contained pieces on alternative medicine and other ‘occult’ subjects.

He also wrote for Guido von List’s (1848-1919), satirical anti-Catholic magazine ‘Der Scherer’ (‘The Pest Controllers’) which later developed distinct nationalist and anti-Semitic undertones (List is sometimes referred to as the grandfather of National Socialism) as the völkisch elements of lebensreform were subsumed by a more strident nationalism.

Ewers interest in the occult would also have been stimulated by his association with writers such as Max Dauthendey (1857-1918), Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915) and Przybyszewski, all of whom had occult/mystical leanings. Dauthendey was connected to the Parisian branch of the Golden Dawn headed by British occultist Samuel Liddel (MacGregor) Mathers (1854-1918) and Przybyszewski edited and contributed to various occult magazines. Ewers dedicated his book Edgar Allan Poe to Gustav Meyrink (1868-1932), the Austrian author best known for his novel ‘The Golem’, (1915) who was a Theosophist and connected to the Golden Dawn. It is said that Ewers contacted an early incarnation of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) in 1906, which had strong links to both Masonry and Papus’ Martinist group. Both The Golden Dawn and O.T.O. are inextricably linked with the controversial British occultist Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), but there is no indication that there was any personal contact between the two until W.W.I when both worked in the U.S.A. for the pro-German propagandist newspapers The Fatherland and The International (both edited by the American author George Sylvester Viereck, 1884-1962) (the author of a 1907 ‘psychic vampire’ novel, The House of the Vampire) and during which time Ewers was also working for the German secret service.

|

| George Sylvester Viereck |

Certainly, Masonry (or at least its followers) had been mocked in Ewer’s 1904 story Die Weise Madchen (The White Maiden) in which various jaded ‘men of the world’, the narrator, a priest, a painter and a newspaper editor, attend a performance organised by Duke Aldobrandindo in which a nude barely pubescent girl tears a white dove apart over her head and is covered with its blood. For the onlookers it is a spectacle with no spiritual content, the editor will use it as a mere gambling aid; ‘“18 = blood, 4 = dove, 21 = virgin ...I will play them this week in the lottery!”’ (The White Maiden).

It is also unknown if Ewers ever used any form of self-hypnosis as part of his creative process. However, there is an intriguing letter to Ewers from Viereck dated January 29, 1918, in which he asks Ewers to collaborate on a projected book calledthe theme of which was to be that of the wandering Jew. In it, he writes: ‘It was begun under peculiar circumstances. You will remember I had asked our mutual friend Professor Müensterberg, [Hugo Müensterberg, 1863-1916, a German-American psychologist and suspected German spy] to hypnotise me so as to make it possible for me to concentrate on the task in spite of the many distractions which diverted my mind in the early days of the war. He consented and under the spell of his suggestion I completed the prologue and the larger part of the first fourteen chapters.’ (Letter dated January 29, 1918. George Sylvester Viereck Papers, University of Iowa.) For reasons unknown the Isaac Laqudem collaboration never came to fruition and Viereck later completed the novel with Paul Eldridge (1888-1982) and finally saw publication in 1928 as My First Two Thousand Years. It is unknown what, if any, Ewers influence remained within it.

What is certain is that Ewers did use various drugs recreationally and as a means of inspiration. By the early 1900s he had begun working on a book titled Raush und Kunst (Intoxication and Art) and whilst this was never completed (an as yet unpublished reconstruction has recently been completed by Wilfried Kugel) an essay of the same title did appear in 1906, which perhaps gives us a flavour of the larger projected work. It is also possible that his essay Edgar Allan Poe (also published the same year) might have constituted a chapter of this volume, as both explore the same theme in similar and, in one case identical, words.

Both essay and book ask the same question: ‘can the intoxication induced by a narcotic help contribute to the creation of a work of art?’ (Intoxication and Art.) The answer: ‘It is not only capable of it but can even under certain conditions spawn completely new works.’ (ibid.) Ewers then lists various drugs and their relation to creativity, such as Hashish — ‘Unlimited refinement of all the senses, the process of spontaneous artistic creation’; Peyote — ‘profusion of images, intense colour scales’; Opium — ‘sculptural vision, incredible lust’; Henbane — ‘postponement of the concept of time, flying’ and Kava Kava — ‘Inner rhythm, capturing the necessity of dance.’ (ibid.) In Edgar Allan Poe, Ewers takes particular issue with Poe’s biographer Griswold, who had suggested that Poe’s drinking had been to the detriment of his creative powers arguing instead that Poe’s alcohol was integral to his creative process . . . ‘because we know that just from this poison which destroyed his body, pure blossoms shot forth, whose artistic worth is imperishable.’ (Edgar Allan Poe.)

In Music in Images, Ewers gives other methods of achieving ecstasy; ‘fasting, fixedly staring, scourging and castigating, suggestion and hypnosis’. Some of these techniques appear in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, but hypnotism especially features in other works too, which indicates Ewers’ intense fascination with the subject.

Both the other Frank Braun novels include trance states. In Alraune, the titular character exerts an uncanny and destructive influence over those she comes into contact with, the story climaxing in a sleepwalking episode, while in Vampire, Braun drifts through much of the central part of the novel in a similar somnambulistic state, unaware of his public speeches or the details of his encounters with various women.

Hypnosis, or something akin to it, is central to his best-known story, Die Spinne (The Spider, 1908), in which a mirroring ‘game’ initiated by the narrator with the woman in the building opposite slides out of his control . . .

‘I clenched my hands and put them in my pockets firmly intending not to move them one bit. Clarimonde raised her hand and, smiling at me, made a scolding gesture with her finger. I did not budge, and yet I could feel how my right hand wished to leave my pocket. I shoved my fingers against the lining, but against my will, my hand left the pocket; my arm rose into the air. In my turn, I made a scolding gesture with my finger and smiled.

It seemed to me that it was not I who was doing all this. It was a stranger whom I was watching.’ (The Spider.)

The femme fatale in this tale is a symbolic Lilith figure named Clarimonde. This choice of name might be Ewer’s homage to Théophile Gautier’s vampire tale La Morte Amoureuse (1836) (known in English as both Clarimonde or The Beautiful Vampire) which Ewers had translated into German in 1902.

Two stories were written around the same as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice which deal specifically with religious ecstasy: Mamaloi (1907) and Die blauen Indianer (The blue Indians, 1908).

The former is a story of Voodoo set in Haiti, in which the (White) outsider finds himself first learning about and then becoming involved with the religion via his servant, and later lover, who is also a mammaloi (priestess). He witnesses a Voodoo ritual led by her and participates in an orgy where: ‘drunk with rum and blood, whipped into boundless lust, [they] tear at each other like animals, throw one another to the ground, lift each other high in the air, thrust their greedy teeth into each others flesh! . . . Two Negro girls fall on me, tear at my clothes. I seize their breasts, throw them to the floor, roll around, bite, shriek — just like all the rest . . . I plunge into the wildest frenzy, into the most unheard-of embraces; leap, rage and shriek, wilder and madder than anybody else.’(Mamaloi.)

A similar scene appears in Chapter Twelve of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice; ‘Carmelina plunged her teeth deep into the round shoulder of the Conaro woman; while the latter embraced the lad with her fevered arm and dug her nails deep into his flesh. They writhed and twisted themselves into a confused knot, encircled each other with their arms and legs and steamed with sweat and blood.’ (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice). Braun later reflects, ‘This wild cruelty which lashed the senses was that whole imaginative process of lower civilization by which man was to be brought nearer to his God.’(ibid.)

Twenty years later, in the travel book Von Sieben Meeren (On Seven Seas, 1927), Ewers, using extremely racist terms, describes Voodoo as the ‘ape religion of the half-brute nigger...built from related elements: a brew of religion, eroticism, and cruelty mixed with a lot of rum and Tafia. Altogether it is revolting and disgusting, rough and ridiculously primitive — not a single metaphysical thought, not a single hint of the honourable children of Satan who imagine the dethronement of the Nazarene.’ (On Seven Seas.)

For Ewers, Voodoo, and by implication, the rite described in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice are merely orgiastic mayhems of the sexes (and races); a chaos which is a world away from the more spiritual androgyny of spontaneity and freedom of true ecstasy.

This also follows the line of argument in Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil (1886): ‘In these later ages, which may be proud of their humanity, there still remains so much fear, so much SUPERSTITION of the fear, of the ‘cruel wild beast’, the mastering of which constitutes the very pride of these humaner ages — that even obvious truths, as if by the agreement of centuries, have long remained unuttered, because they have the appearance of helping the finally slain wild beast back to life again . . . Almost everything that we call ‘higher culture’ is based upon the spiritualising and intensifying of CRUELTY — this is my thesis; the ‘wild beast’ has not been slain at all, it lives, it flourishes, it has only been — transfigured.’ (Beyond Good and Evil.)

In The Blue Indians (written in the same year as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice) the unnamed narrator travels to a region in south-west Mexico searching for a tribe of blue Indians who can allegedly recall past lives. What begins as a relatively harmless psychical research project, results in a young girl named Teresita (the Spanish diminutive of Teresa) being overdosed with Peyote (‘enough for half a dozen strong men’) by her father, who ‘knew with true instinct that Teresita would only speak out of such a very heavy memory while in a state of ecstasy’. In the resultant trance the girl recalls a past life as a German Franciscan priest who with ‘sabre in his right hand and cross in his left’ raped, burnt and killed many of the tribespeople during the Spanish conquest of the area in the 1520’s. As the priest tells his story (in ‘a broad old Low German’ which Teresita could not know), he forces the girl’s father to bite off his own tongue.

‘ “Come here you old heathen dog! Your damned tongue has prayed often enough to your shabby devil gods before I brought you the Holy Virgin and salvation! Out with your blue monkey tongue that cries out to Tlahuiccalpantecuhtli, your lousy Pulque goddess, Coatlicue, Iztaccihuatl and Tzontemoc, the filthy sun god that runs through the underworld. Out with it, out with it! Bite it off, bite your damned tongue off!”

|

| Cover of a later (1921) edition of 'The Blue Indians' |

He struggled weak-minded against this horrible compulsion the white priest had laid down on him, this hellish compulsion of a murderous priest long since dead that had awakened and sprang across the centuries to once more utter that handful of fearful words that held the Elder in nameless torment.’ (The Blue Indians.)

Teresita’s ‘low German’ is echoed in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice where Giovannni Ulpo quotes Revelations 19:20 in Latin, an event which Braun rationalises as ‘a reversal to some ancestral mental field — like everything else in this valley.’

For Ewers it is not the source of the intoxication (natural or artificial) that is important, but the resultant ecstasy and how it can be used; ‘The real issue is whether this ecstasy remains unconscious or can be brought into consciousness and worked with...the artistic process of working through intoxication and bringing art into conscious awareness is gained only later after both the intoxication and the emotions are gone. Short sentences, words and symbols written down while intoxicated are often enough to call up, even years later, the entire sequence of memories and images of the original experience.’ (Intoxication and Art.)

He expands further by saying that ‘bringing material out from the subconscious into consciousness and fashioning it into art is something that only a person of high intelligence combined with strong talent is capable of’ (ibid) because ‘godlike intoxication alone does not create an absolute work of art . . . the common work, the despised technique, the reflection and polishing, the weighing and filing, are quite as indispensable for its perfection.’ (Edgar Allan Poe.)

Finally, and these lines are exactly the same in both Intoxication and Art and Edgar Allan Poe, ‘Is there a more shameful lie than that remark of the banal: “artistic creation is not work — It is a pleasure?” He who says this and the great public which thoughtlessly repeat it, have never felt the breath of ecstasy, which is the only condition demanded by art. And this ecstasy is always a torture, even when — in rare cases — the cause which produced it, was one of rapture.’

In the first chapter of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Braun and the priest Don Vincenzo talk about a Paduan preacher Vincenzo Alfieri, who has oratorial abilities but lacks inspiration; ‘they will remember all their lives how he spoke. They have all forgotten what he said! That beast is there, that splendid mighty creature — but it can neither run nor bite!’ (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.)

Vincenzo then compares Alfieri to Pietro Nosclere (an original inhabitant of the valley who had spent time in America), another weak preacher ‘quite like the salvation army’ but has still created a following because it is so dull within the village. ‘there is never a definite idea involved. No one knows what he really desires. It is a harmless illness of the mountains, nothing more. My Bishop calls it “Valley Fever”.’(ibid.)

Braun realises that Nosclere and the Val di Scodra are ideally suited to his desire to test his manipulation theories as ‘there lies a certain power in the deep valleys of these mountains — a mysterious, ecstatic, Mystical power. And year after year it is wasted in the smoke of a wretched blaze of straw. One shouldn't let such a power lie barren.’(ibid.) Even though it has potential for disaster, Braun, concerned only with his experiment and ego, will go ahead anyway and legitimise it as part of his quest for greater knowledge, saying in relation to Pietro Nosclere that ‘he doesn’t even need to understand. If only he becomes capable of that creative act! If only he can wield his mountaineers into a single mass, as the Paduan preacher did. I want that beast, that mighty beast, don Vincenzo. Trust me I will teach it to bite.’(ibid.) In Chapter Four he will say to Teresa ‘Perhaps you’re only stupid, commonplace, hysterical fodder for the clinics of curious physicians! For, look you, my child, on that stage where I am master there is no room for the trivial! The actions must be tragic and fatal and significant!’(ibid.)

Throughout the novel Ewers emphasises how the inhabitants are almost universally backward, brutish, ignorant and avaricious. ‘Each has some infirmity: one is crippled in body, another in soul . . . Think — they don’t think at all, these cave-men of the mountains. They do not even dress. They scarcely live; they vegetate like decaying fir trees. Their skulls are small and flattened, deformed goitres hang from their necks.’ (ibid.)

It appears that Ewers is satirising the ‘degeneration theories’ promulgated by social scientists such as Benedict Augustin Morel (1809-1873) and Cesare Lombruso (1835-1909) that were bought to popular attention by Max Nordau’s (1849-1923) hugely influential 1892/93 book Entartung (Degeneration).

These social Darwinists suggested, among other things, that the increasingly urbanized nature of society removed the human race from the natural environment, thus reducing the impact of natural selection. Urban life with its crowds and noise caused both physical and societal sicknesses (such as hysteria) which were fuelled by things such as ‘socialism’, sexual emancipation (including education for women), and ‘modern’ literature that dealt with unsavoury/degenerate topics such as drink, drugs, sex etc or used a non-narrative ‘modernist’ style.

The physical descriptions of the Val di Scodra inhabitants, the brutal farmhand Scuro, and Venier (the ‘dirty, stunted, black-haired fellow, with a low forehead’) include a widely recognized ‘attribute’ of the degenerate, the goitre, and would fit Lombruso’s famous composite images of urban ‘criminal types’ — a world away from the romanticised rural idylls portrayed in much of the period’s mainstream literature.

Ewers firmly believed that ‘The path of humanity, despite individual rough spots, is consistently leading upwards. How much higher we stand than our ancestors and even how much higher still our descendants will stand than us!’ (Music in Images.) and that ‘It is an eternal war with eternal defeat if we do not gain victory over our ancestral memories. We are slaves to the ideas of our forefathers. We spend our lives tormenting ourselves in their chains, suffocating in the restrictive fortress that our forefathers have created. We need to build a bigger house. When we are dead it will be worn out as well and our grandchildren will lie in the chains that we have created.’ (The Blue Indians, 1908.)

The hypnotic/ecstatic episodes within the novel are an amalgamation of elements and cases found in various volumes written by the Charcot circle and the Salpétriere is explicitly mentioned in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice in relation to Teresa’s stigmata: ‘If it had not been performed in public, it had been performed in the medical laboratory. Nancy and the Salpétriere knew it well, and had observed many transudations of blood among hysterical patients.’

Nosclere is a neurotic whose religious zeal even has him preaching and praying in his sleep. Braun exploits this vulnerability by planting the suggestion that it is the soul of Elijah that causes him to walk at night.

Nosclere’s subsequent somnambulistic knife attack on Braun appears to have been largely lifted from Gille de Tourette’s L’hypnotisme et les états analogues au point de vue médico-légal (Hypnotism and similar states from the medico-legal point of view, 1887). Compare:

‘One day I had not lain down at the accustomed hour but was working . . . when suddenly I heard the door to my room open, and a moment later the lay brother entered in a state of deep somnambulism. His eyes were wide open but fixed . . . he had a long knife in his hand, walked directly over to my bed . . . and it appeared that he was making sure by running his hands over the bed that I was there. Then he struck three deep blows and . . . cut deep into the mattress . . . when he had struck his blow and turned around, I could observe...that his face . . . bore an expression of gratification.’ (‘L’hypnotisme . . . ’ quoted from Stefan Andriopoulos’ Possessed — Hypnotic Crime, Corporate Fiction and the Invention of Cinema, 2008) with:

‘Frank Braun stood beside him . . . but the somnambulist gave him not the slightest cause to lift his hand, it was entirely clear that he saw and heard absolutely nothing. . . Pietro strode straight up to the bed that stood by the window, held the knife between his teeth, and with both hands felt carefully for the head of the bed. The bright gleam of the lamp fell into his face and Frank Braun saw how contorted it was with measureless rage.

Finally he seemed sure of himself, he grasped the pillow with his left hand, took the knife, and thrust out with the strength of madness. Once again he lifted the knife high, and once again he gave a thrust, then he wiped his eyes with his hand as though the blood had spurted into his face. And again and again, he buried the knife up to the hilt in the pillow.

A smile of profound inner satisfaction settled on his lips.’ (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.)

Teresa’s hypnotic and ecstatic episodes also follow Charcot’s approved sequence of a grande hystérie attack complete with tropes such as the arc de cercle where the head and body arch back as far as they can. Braun tests her by driving a needle into her arm, a method also used at the Salpêtrière demonstrations to demonstrate anesthesie hysterique. The doctors would no doubt have been aware of the role that pricking also played as a method for the testing of witches.

|

| ‘Arc de cercle’, from Paul Richer, Études cliniques sur l’hystéro-épilepsie ou grand hystérie (1885). |

Intensely religious, she believed walking on tip-toes was a prelude to her imminent levitation into heaven. Perhaps significantly for Ewers, ‘Madeleine’ also exhibited stigmatic bleeding from her hands and feet; something that Janet himself could not satisfactorily account for.

There are also similarities between Teresa and Charcot’s patient Genevieve Basile Legrand (1843-unknown), another intensely religious hysteric who had visions of a psycho-sexual nature and had experienced a psychosomatic pregnancy at the age of sixteen. Bourneville would strangely term her a ‘succubus’, a term used for a female demon believed to have sexual intercourse with sleeping men. I believe that he meant to imply that her visions would have been religiously interpreted as sex with its male equivalent an ‘incubus’. Braun uses the latter term in relation to Teresa’s ecstasy but later comments, ‘Pshaw, it was something great only for the artist that lived in his eye, but something very inconsiderable for the scholar in his brain.’ (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.)

Geneviève strongly identified with two figures, one being Louise Lateau (1850-1883), probably the most famous (and investigated) stigmatists of the late 19th century, who Geneviève called ‘her sister’ and even attempted to visit around 1876. The other was Jeanne des Anges (1602-1665), the Mother Superior at the centre of the demonic possession/mass hysteria at Loudun, which was also Genevieve’s birthplace.

|

Louise Lateau in ecstasy (1877). Photo by Ernest Lorleberg (1835 -1908) |

Jeanne’s autobiography had only been rediscovered in 1884 by two doctors at the Salpêtrière (Gabriel Legué and Gilles de La Tourette) and was published as part of the Bibliothèque diabolique series in 1886 as the Autobiographie d'une hystérique possédée (Autobiography of a Possessed Hysterical). In 1910, one year after The Sorcerer’s Apprentice was published, Ewers would write a short introduction to the first German edition, Soeur Jeanne. Memoiren einer Besessenen (Sister Jeanne. Memoirs of a Possessed).

|

| Cover of 1911 edition |

After acknowledging that the autobiography is a self-aggrandizing document, he states that he believed Jeanne was a ‘hysteric’ and perverted, manipulating the church authorities to gain personal power, ‘Certainly sometimes she helped a little — is there a hysterical woman who does not do it with her illnesses?’ (Soeur Jeanne.)

This comment would appear to be a condensed paraphrase from Chapter Three of another Bibliothèque diabolique volume, Bourneville’s Science et Miracle: Louise Lateau ou la Stigmatiseé Belge (Science and Miracle: Louise Lateau or the Belgian Stigmatist, 1878), where, after comparing Lateau to patients at the Salpêtrière, he states ‘like all hysterical women, it may very well be that [Louise Lateau] is deceptive — and sometimes in good faith — and that she lets herself be induced into exaggerating the phenomena she exhibits, seeing the importance that they have in the eyes of her intimate advisors.’(Science et Miracle.)

In Ewer's novel, Braun cynically speculates upon how he can turn Val di Scodra into a destination of pilgrimage similar to Lourdes and the even more recent Sanctuary of Pompeii, which had come into being when an ex-Satanic priest Bartolo Longo (1841-1926) who had subsequently seen the error of his ways and converted, discovered a picture of the Virgin in a Naples junk shop which, when installed in a small church in Pompeii began to work ‘miracles’ and by 1901 had become a major Marian shrine. Bartolo was beatified by Pope John Paul II 1980.

|

| Bartolo Longo |

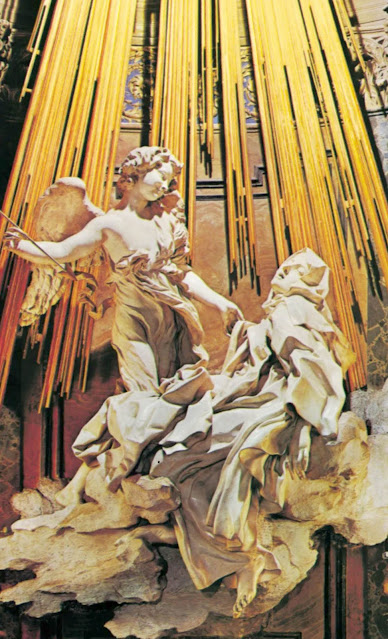

This reference is to Saint Teresa of Ávila (1515‐1582), the Spanish mystic and author of one of the great spiritual books of the Catholic faith, The Interior Castle (1577). In it, she describes the vision of her own union with Christ, in which a Seraphin pierces her heart with a golden dart ‘in such a way that it passed through my very bowels. And when he drew it out, methought it pulled them out with it and left me wholly on fire with a great love of God . . . . It is not bodily pain, but spiritual, though the body has a share in it — indeed, a great share.’ (The Interior Castle). This is similar to The Sorcerer’s Apprentice where Braun tells Teresa that ‘the strangest thing is that the most frightful suffering is transformed into the highest rapture.’

This is the moment captured in Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s (1598-1680) famous statue The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1645-1652), which was controversial from its unveiling for its overt sexuality. In The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Braun refers to the saint (or the statue) at the moment of Teresa’s rapture ‘like the holy lady of Ávila in the enjoyment of an angelic embrace.’

|

| Bernini - The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa |

‘Madeleine Lebouc’s’ visions were also highly erotic, as ‘she compares herself to Mary Magdalene kissing the feet of her saviour and feeling as though ‘blood flowed into my mouth, intoxicating me, and Jesus resuscitated came into my arms,’ (quoted in Richard D. E. Burton’s, Holy Tears, Holy Blood: Women, Catholicism, and the Culture of Suffering in France, 1840-1970, 2004) and, while she is flying, ‘the pleasures that I feel in my mouth are almost continuous, I have the sensation of a perpetual kiss . . . my being is purified, transformed, divinized. I participate in the essence of God, I am in God.’(ibid.)

Teresa’s ecstatic episode appears to be a blasphemous reconstruction of The Interior Castle, with overtly sexual elements drawn from Salpêtrière and a reminder to the reader of her rape by Braun the sorcerer: ‘Now she leaned back, lying flat, with her head supported against the wall. And gently, scarcely noticeably, she raised her body under the linen that hid them, drew her legs apart. Her mouth opened and closed as in kisses, a deep sigh of ardent happiness issued from between her white teeth....’(The Sorcerer’s Apprentice). The ‘beautiful Seraphin’ is represented by the little boy Gino, an ‘innocent’ who would die a ‘sacrificial death for the Lord’ in the next chapter.

|

| Mahlon Blaine produced an eroticised version of the illustration in in Sorcerer's Apprentice as part of his privately published portfolio Venus Sardonicus (1929). |

By Chapter fifteen he realizes ‘He was incurable; never would his longing be fulfilled. His impassioned longing for the mask which he loved so well. And yet — perhaps — ? Some day — in the end — in madness? Then, then, at last, his thoughts would be free of the terror of knowledge. Then would the chain be broken which his reason had forged. Then would his will range, free and glad, and shatter worlds and create them — Yes, then! Was it not best to be mad?’ (ibid.)

Given all of the foregoing, one might be forgiven to think that Ewers has no time at all for the Christian mystics.

However that would be wrong, for within the novel he positively refers to both ‘Sister Kateri’ (aka Sister Catherine, c. 13th century) author of The Sister Catherine Treatise, a mystical text formally attributed to ‘Meister Eckhart’, (Eckhart von Hochheim, c. 1260-1328). Neither would be found within Der Heiligen Leben (The Lives of the Saints, compiled ca.1400), the book that Braun loans to Teresa (and which Geneviève was said to have read avidly at the Salpêtrière), as both were at that time considered heretics.